The new-look, state of the art Eastlands Stadium took centre stage as the race for Champions League football came to a head on May 1, 2010. Manchester City versus Aston Villa – both backed by new money were going toe-to-toe on and off the pitch to realise the lofty ambitions of new investors.

Donning his garish, yellow Puma boots, the towering John Carew was the familiar foil for the speedy Gabriel Agbonlahor as Martin O’Neill’s Villa plotted a Premier League best season-ending for over a decade.

O’Neill’s Villa were level pegging with Tottenham Hotspur – who occupied fourth place on 64 points – before Norwegian Carew momentarily forced Villa into the top four after his goal in the 16th minute. Villa had been dining at the top of the division for the first time since the days of Ron Atkinson and Brian Little in the dugout, ten years before O’Neill set out to restore Villa’s place among the European elite.

A genuine assault on the Champions League places would, however, prove futile as a Carlos Tevez inspired City put three more past Villa on a day that would dramatically alter the club’s recent history and Carew’s career.

His goal in Manchester had put Villa in the top four driving seat before City completed a comeback, leaving Villa numb on a canvas of uncertainty and quandary. Both clubs have since taken completely different paths in an era where a sudden lurch into the unknown can be met with catastrophic repercussions.

A post-season hangover following the failure to realise Randy Lerner’s expensive goal would turn into a decade of turmoil for Villa. He might not have known it at the time, but as Carew wheeled away in celebration at the Manchester City stadium, it would be his last, despite ending the 2009-10 campaign as the club’s top scorer.

The following summer transfer window would offer little rest-bite for a board under pressure from O’Neill determined to strengthen, certainly not lose his prized assets, following the loss of Gareth Barry to top-six rivals Man City the summer before. But the same patterns would soon follow when Stephen Ireland gave way for James Milner to kick-start City’s attack on English football’s upper echelons and Villa’s demise.

It was the final straw for O’Neill, who on the cusp of the new league season opted out of Lerner’s quickly fading ambition.

As speculation and discontent swept across Bodymoor Heath in the weeks leading up to the Premier League’s new season start, Milner’s future was known, but that of head coach O’Neill’s wasn’t. Carew and Co. hadn’t even finished their day’s work on the training pitch before O’Neil dumped a pre-prepared letter of resignation on Paul Faulkner’s desk.

For Carew, a player so focal to O’Neill’s famed direct style of play, his days at Villa Park, despite all he’d achieved in three memorable years with the club were numbered. In fact, six months after O’Neill’s walkout on the new season’s eve, Carew was out the door too.

His career, nomadic to say the least, would continue to thrive away from Villa Park, but perhaps in ways unique to Carew after he hung up his fluorescent Pumas for good. Instead of snuggling up to a Sky Sports sofa, or prowling a touchline, the Hollywood lights would beacon for the Norwegian.

An acting career is now in full swing for the man partial to admirers to both personality and footballing ability, even dates with royalty would follow, but not before a career on the pitch that’s taken the striker from the southern Norweigan shores of Trondheim Fjord to UEFA Champions League finals in Europe’s most alluring landmarks.

With trials and tribulations aplenty here’s the story of John Carew, Carew!

John Carew making a name for himself in Norway

He’s bigger than me and you and that hasn’t been truer even since Carew burst onto the scene as a raw striker from hailing from the outskirts of Norway’s capital city, Oslo.

The many neighbouring municipalities of district Akershus were home to Carew, who joined Lørenskog IF as a schoolboy. Surrounding minimalistic housing and pine trees wrap the Rolvsrud Stadion in your typical picturesque Scandinavian scene – the very setting for Carew to make an early name for himself.

Starting out at the same club as fellow former Premier League player, Henning Berg was enough traction the young forward needed to force a move to local professional side Vålerenga after making an impression at Lørenskog. Born to a Gambian father, a one-time goalkeeper, and a Norwegian mother, Carew’s reputation quickly grew and a move to the capital inevitably followed.

Vålerenga, of Oslo, are a big name in Norwegian football but one that had fallen from grace in Norway’s elite football before signing Carew in 1997. In that same year, he was part of the team that gained immediate promotion back to the Tippeligaen, Norway’s top division and also won Norwegian Football Cup.

Carew was years ahead of his own physical prowess and goal-scoring knack. His ability at such a tender age was even too early for Vålerenga’s Tippeligaen rejuvenation after securing their top-flight status once again.

Social policy in Norway both at the national and local level has helped emphasise a connection between football at the mass and elite levels and now we’re seeing Norway move into a potential golden generation of football stars of modern times – Carew might’ve missed that boat or even a change of career pathway altogether.

Vålerenga’s new state of the art Intility Arena, which opened in 2017, boasts some of Norway’s modern architecture and with fresh investments, Vålerenga finished in a respectable fourth place last season. Virtually every municipality in Norway has built year-round facilities to cope with harsh Scandinavian winters and crisp summers, but Carew didn’t stick around for long after helping Vålerenga back in the Norwegian big time.

During his two-year period at the club, he played 58 matches and scored 30 goals, while his profile rose even more due to his combination of strength and goal scoring ability – with comparisons to that of Erling Braut Håland’s start to life in Europe over recent seasons.

Though, Carew wouldn’t settle for home comforts – that a common theme in his unique career. Moving 240 miles north of Oslo, to the country’s fourth highest populated city, Trondheim. The highly-rated forward would rack up moves across the continent in a stellar career, but he’d still get a taste of Norwegian football royalty even if it came before his 20th birthday.

It was the summer of ’99 that Carew joined Norwegian football’s most successful club and Champions League mainstays Rosenborg BK in a deal worth 23 000 000 kroner. Carew was part of a formidable Troillongan that finished first in their UEFA Champions League group, in a memorable campaign that included a 0-3 away win against Borussia Dortmund.

Scoring 19 goals in only 17 games and a further five in the Champions League, was part of an extraordinary rise for Carew that would later be capped with a move to Spanish giants Valencia – though nothing was certain in his career.

The word that is said to mean “strength” in the Gambian homeland of Carew’s father, “alieu” is even part of Carew’s DNA. John Alieu Carew, the striker who would later tear up divisions across the continent wasn’t always guaranteed to put balls in the back of the net.

His Dad, Ousainou, was keen for him to follow his footsteps and become a professional goalkeeper.

“My father played football too a long time ago and on my father’s side of the family there were a few footballers,” Carew told the Sunday Mercury.

“He was in goal and he introduced me to football. He played, not what you would call professionally, but he played for the Gambian national team in Africa but it was not professional at that time.

“When you are younger you decide what you want to be and I wanted to be a striker which was a bit controversial for him I think!”

Vålerenga to Villa: Carew’s nomadic playing career

It was the Champions League that served as the platform for the big Norwegian to catch the eye of many suitors from across Europe, but no project was more exciting than that of Valencia’s on the Iberian peninsula.

For the first time in Valencia’s history, the Spanish club had reached the European Cup final in the 1999-2000 season. Losing 3-0 in Paris to Spanish rivals Real Madrid was to be a farewell for influential forward Claudio López.

Valencia sought after a replacement for their talisman, and while Carew wouldn’t get to play alongside the Argentinian in Héctor Cúper’s side, he would benefit from the mastery of Pablo Aimar when the playmaker signed on in January – becoming a staple of Valencia’s dominance of the early 2000s in La Liga. Didier Deschamps and Gaizka Mendieta were also part of the side that would soon rely on Carew to shoulder his weight of goals and enjoy some successful years with Los murciélagos.

It was an €8.5 million transfer fee that won Carew under the nose of some of Europe’s elite clubs, but the Norwegian would first experience bitter heartache before joy at Valencia. Following the club’s first Champions League final appearance, a successive final would await.

Arsenal had succumbed to Carew’s Valencia in the Champions League quarter-final stage, before more English opposition in the form of Leeds United were then the victim of a quality Valencia side that included an ever-improving Carew.

Losing his first European final to Bayern Munich was the grounding Carew had to take, whether he fully realised his potential after appearing at a final at 20 years of age is however up for debate. Scoring in a penalty shoot-out on the grandest of stages and holding his nerve is something nobody will take away from Carew – an agonising defeat in the 2001 Champions League final to the German giants a sickening blow for the young forward.

Carew had to earn his place a side brimming with attacking quality from day dot. Led by the enigmatic Cúper, the Valencia squad at the time featured a host of attacking stars in Mendieta, Vicente, Zlatko Zahovič, Rubén Baraja and Adrien Ilie. Aimar immediately secured a place in the side after joining in January, supplementing the industry of David Albeda, the creation of Baraja and eventually the power of Carew.

When Cúper left the Mestalla after a successive Champions League heartache, Rafa Benitez was drafted in after making a name for himself with lower league Spanish clubs, Real Valladolid, Osasuna and Extremadura. His influence was profound, winning two La Liga titles in three years, but Carew’s impact in his team was limited.

The Valencia squad when Benítez first arrived was itself not short on quality and there was plenty of potential within it. Many of the team that played in the 2001 Champions League final under Cúper would remain crucial members of Benítez’s double league-winning side. Benítez, however, did make some significant signings in his first year, perhaps the most important of the players he bought is the one he took from his former club Tenerífe, striker Mista, to Carew’s frustrations.

The Spanish forward was something of a protégé of Benítez’s having brought him through when the assistant manager of Real Madrid, and he went on to perform an indispensable role as the lone striker, having been preferred up front to Carew and Juan Sánchez. Tactically, Benítez’s most important change was to switch from a 4-4-2 diamond to a compact 4-2-3-1, pushing Carew away from the Mestalla after only 12 months at the club.

Carew’s second season under Benítez was more productive, scoring 13 goals as the club’s top scorer despite the team finishing in a lowly fifth place. Carew was once again responsible for Arsenal’s exit from the Champions League in that 2002-03 season as the Gunners lost their all-important final game of their second group phase in Valencia. Carew’s double either side of a Thierry Henry strike would be the Norwegian’s parting gift for the Spanish side who he left for Roma on a season-long loan for the 2003-04 campaign.

Looking to settle on the continent

Surplus to requirements in Benítez’s Valencia system, Carew was keen to secure regular playing time ahead of a potential EURO 2004 appearance with Norway, but Spain would prove very difficult opposition as the tournament’s play-off draw was made in Frankfurt. Henning Berg’s own goal gave the Spanish a slender advantage before Carew’s Norway took a heavy 3-0 loss in Ullevaal Stadion – where the striker began his career with Vålerenga.

Nevertheless, Carew’s search for regular game time was whittled down to a Seria A side, A.S. Roma. Fabio Capello’s fifth season as the boss of the Giallorossi was his second best. Having won the Italian title in 2001, a second-place finish in 2004 was enough to qualify for the Champions League behind AC Milan – one of only two Seria A titles the Rossoneri have won this millennium.

Though, Carew hadn’t quite taken to life in Italy as first hoped. Scoring seven times in 26 games wasn’t the return he’d expected for having been promised game time along with the imperious Francesco Totti. Falling into off the field disputes didn’t help his cause either.

The then Roma boss hasn’t been too averse to the odd bout of fisticuffs in the past, as Paulo Di Caniz can testify, so when Carew was caught up with John Arne Riise on international duty, Capello couldn’t have many complaints about his actions.

Neither Capello nor Carew are men to be crossed, but such was the latter’s anger when Riise spat on Carew’s boots at a Norway training camp, when the squad boarded the team coach he sought out the former Liverpool man and caught him with a right hook to knock him out cold.

Carew’s Italian job, marred by some misconduct and an equal share of starts and substitute appearances, was one to forget – he was eager to start afresh. But not before another year’s worth of new experiences further afield, this time to one of Europe’s thriving leagues.

Football in Turkey has a proud history, which stems back to the late 19th century when Englishmen brought the game to Salonica, a first-level administrative division of the Ottoman Empire. The first league competition was the Istanbul Football League, which took place in 1904, and since then, Turkish football has evolved through several variations until the creation of the Süper Lig in 1959.

While Turkey’s elite sides Fenerbahçe and Galatasaray are both majorly responsible for the country’s healthy UEFA coefficient, Carew’s next team, Beşiktaş are the third giant of Turkish football based in the capital, Istanbul.

When Carew joined Beşiktaş in 2004, former Real Madrid coach Vicente del Bosque had only just got his feet under the table in hope of reviving Besiktas’ fortunes after the club ended the 2003-04 season in a disappointing third place.

Carew’s 14 goals in 28 games for the Black Eagles, including a goal in each derby with Fenerbahçe is about as good as it got for the Turks and Carew.

Beşiktaş probably drew more games than Carew changed his haircuts, and that was a high number as the striker went from corn-rows to buzz-cuts in months. Del Bosque’s side finished 11 points behind league champions Fenerbahçe in a season that would turn out to be their joint-lowest league finish for a decade, as Carew could only help his team to a fourth-place finish.

Only two years before Carew and del Bosque joined Beşiktaş, the club had won their tenth Süper Lig title in 2002, but the Norwegian wasn’t keen on waiting around waiting for the 11th championship as he packed his bags in search of new opportunities again.

Del Bosque would soon take up the Spanish national team gig, and the manager leaving Turkey was a key factor in Carew leaving to join Olympique Lyonnais in a deal with up to €7.6 million despite intense interest from coming from the Premier League. Fulham and West Brom had both failed in attempts to sign him before Carew signed for Lyon, managed by Paul Le Guen, who was embarking on his first season with the French champions.

Carew was joining another club – his first after playing with Valencia – who were at the top of their domestic league, having won four Ligue 1 titles in a row. Lyon were dominating all in France, in a comparable fashion to that of Paris Saint Germain’s current hold on domestic fronts.

After scoring eight goals in a team more reliant on Carew’s ability away from simply goal-scoring duties, it was a productive return for the forward, whose unique role in Le Guen’s system helped retain the league title once more, winning a fifth title in a row.

Carew’s love affair with the Champions League had no sign of letting up either, as he netted four times in eight starts with Lyon, including goals in memorable wins for different reasons in the group stages against Real Madrid and Rosenborg – his old side as a teenager. Reaching the quarter-final stage, but losing out on a final four place to AC Milan was another setback in Carew’s search for European glory, but there was no lack of domestic silverware in his cabinet back home.

Lyon would pick up a sixth successive league title in the 2006-2007 campaign, but Carew wouldn’t claim his second Ligue 1 medal as he departed the Stade de Gerland in January – but not before smoothing over a few cracks with some former employers.

Carew was hardly involved in Lyon’s starting eleven’s for his second Champions League campaign with the club, but he still had time to make an impact against the European elite. Namely Real Madrid, then coached by his former Roma boss Capello, Carew scored on what was his first appearance in the competition that season, helping Lyon qualify for the knock-out stages at the Bernabéu in 2006.

Madrid boss Capello called Carew “a great player” after he came back to haunt him with Lyon. Though, only two months after scoring the opener in a 2-2 against the to-be La Liga champions that season, Carew’s next move would turn out to be the making of his career, one that influenced his life away from football in the years to follow.

Forever a cult-hero at Aston Villa

In a swap deal for Milan Baros, who Villa had picked up in a deal worth £6.5 million in 2005, Carew and the Czech traded places – Lyon for Birmingham, the Rhône river for Birmingham’s canals.

But it was a club going places under new, ambitious investor Randy Lerner. Villa, with one of the most exciting British managers in the game, O’Neill, he was keen to build around a traditionally British core of players, with the exception of the Scandinavian few, Carew, Martin Laursen and Olof Mellberg.

“It was the whole package,” Carew said after signing for Villa in January 2007.

“There is big potential here with exciting months ahead and young, talented players and a great manager. There is no reason why we can’t build on that and reach our goals and be in the top five, six or seven in the short term. We’re going in the right way.

“I do like the English game, You just have to get used to the pace and over time I can use more of my strengths. I prefer it here. You have chances, it’s better for the spectators and there is more entertainment.”

Carew was keen to back up his words, and sizable reputation from the continent to apply himself in the most competitive league of them all. Memorable moments aplenty for Carew and fans alike, from second city derby spoils to top-flight hat-tricks, he scored 31 times in his first two and a half years at Villa, before netting 17 in the 2009-2010 campaign – ending that season as the club’s top scorer.

O’Neill’s eve-of-season departure in 2010 had infuriated the Villa Park power-brokers, and possibly none more than Carew and Stiliyan Petrov amongst the playing squad. Petrov, a midfielder typically deployed by O’Neill in systems to suit the Bulgarian after formally being together at Celtic, was one major victim of the manager’s dramatic walk-out.

Carew, on the other hand, was simply a casualty having enjoyed the best years of his career under the Northern Irishman.

“My parents live in Norway but they come over every once in a while and see a match so they’ve seen me score a goal for Villa,” Carew fondly remembered.

“Both my mum and dad have been a big influence and they have always been interested in what I’m doing.”

Aston Villa was a part of Carew’s family, and little did he know at the time, he’d continue to hold dear the club in most walks of life he took after his playing days were up. Carew’s time at Villa was all but up with ongoing rumours in the press about a dispute between himself and new Villa boss Gerard Houllier, who had been leaving Carew out of the matchday squad to work on his fitness.

Darren Bent’s record-breaking move to Villa Park only five months after O’Neill’s departure was, however, the final nail in the coffin for Carew and his time at Villa Park. Loan moves Stoke City and West Ham would follow after his release from Villa in 2011, but in 2013, the Norwegian announced his retirement from the game.

O’Neill and Lerner’s failure to qualify for the Champions League with Villa proved to be a critical juncture in Carew’s career on the pitch, but a catalyst for life away from it also.

When a football club loses their coach just before the start of the league season, the players must pick themselves up in an award-winning drama filmed in the sub-conditions at Ulsteinvik, Scandinavia.

Carew knew this plot all too well but not In front of the cameras. It’s funny how life plays itself out, but for Carew, coming to terms of O’Neill’s walkout, little did he know that such an impact would open new doors, as one had seemingly slammed shut on his playing days.

So when he strolled onto the scene of a brand new Norwegian blockbuster ‘Home Ground’ to act against a role inspired by former coach O’Neill – who clearly played such a crucial part in his footballing career – he was well versed in this script but not necessarily by means of acting.

Life after football: from set-plays to plays

Turning Villan to villain on set, you might not have been surprised to see Carew star in multiple Norwegian blockbusters, but using his life in football as inspiration is about as unique as it comes for film directors.

The Hollywood lights, in fairness, have always been calling for Carew, a personality comparable to few others in the game, and he wasn’t letting Vinnie Jones’ failed career in the movie industry prevent him from trying to go one better.

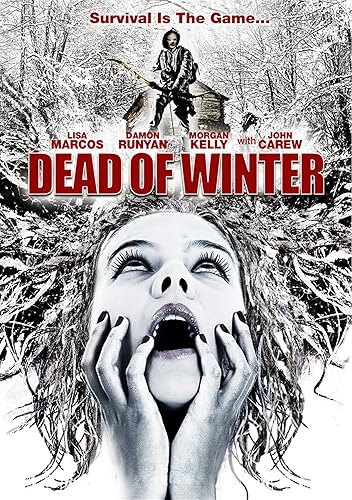

The 41-year-old has only been out of the game for almost eight years now but has already featured in four movies since 2014, and several TV series’ and shows. After landing a role in Robert Rice’s Dead of Winter as his first acting appearance, Norwegian film Hodvinger was Carew’s chance to battle with the Albanian mafia. Though his most prominent movie, and one that resonates with his career at Villa under O’Neill, was Home Ground.

The 41-year-old has only been out of the game for almost eight years now but has already featured in four movies since 2014, and several TV series’ and shows. After landing a role in Robert Rice’s Dead of Winter as his first acting appearance, Norwegian film Hodvinger was Carew’s chance to battle with the Albanian mafia. Though his most prominent movie, and one that resonates with his career at Villa under O’Neill, was Home Ground.

The series, stretched over two seasons covers a football club dealing with the loss of their coach before the start of a new season. With over 1,619 user reviews on IMDB, Home Ground was voted at a very respectable 8.00/10.

Carew even formed a little niche as an on-screen gangster after his roles in Dead of Winter and Hodvinger, as he promoted on his Instagram to his 60,000 followers. That celebrity life is in the DNA of the Carew’s, though that might not come as a surprise.

Sister Elisabeth is a prominent singer-songwriter in Norway. After promoting EP’s in Los Angeles, she auditioned to represent her country at the Eurovision finals in 2014 in the Melodi Grand Prix. Elisabeth Carew made the final with her song “sole survivor” but eventually lost out to Carl Espen in the final.

The Norwegian entry, selected through the national Melodi Grand Prix competition was organised by the Norwegian broadcaster Norsk rikskringkasting (NRK). Norway was represented by the song “Silent Storm” performed by Espen and finished in 8th place in the finals, scoring 88 points, for the Carew’s it was a shame not to see one of their own represent their nation on the world stage again.

Proud of his tight-knit family, Carew has always been supported to the nth degree in whatever project he pursues. Life after football had firstly brought about a new career in the world of acting but not before making some close acquaintances with quite possibly the most well-known family of all.

“I did well in my home country, you know!” Carew reminded the press when images had circled of he and Prince William, the future King of England celebrating Jack Grealish’s stunning, match-winning volley against Cardiff City in 2018.

Both William and John would share a box at Villa Park, in what was the Prince’s second visit to the stadium, after first visiting to witness an uninspiring performance by Paul Lambert’s Villa in the 0-0 home draw against Sunderland in 2013.

Pictures and even videos of his celebration went viral, and William’s new “bromance” with Carew was for all to see.

Carew revealed: “We decided to go and support our team before the end of the season. He invited me to join and it was a great honour. He’s very enthusiastic and he really loves his football. I’m proud because I’m a Villan and so it was good to watch the game together.”

With Carew by his side this time around, it was bound to be more exciting than a 0-0 on and off the pitch even if Bruce-ball was in full might’ve been in full flow against Neil Warnock’s Cardiff. That season, Villa would fall a game short of promotion back to the Premier League after losing to Fulham in the play-off final at Wembley, but a year later under Dean Smith, Carew and William were in each other’s arms again as the fallen giants got back to their feet.

Humbled in awe, Carew agreed with William who suggested the two then make the visit to Wembley to watch Villa’s 2019 play-off final against Derby County, with Villa prevailing 2-1 at the national stadium.

It seemed that Prince William and Carew, the former Villa striker, had actually known each other for a while. Speaking to Soccer AM in 2019 about meeting the royal, John explained: “He was in Norway a few months ago and I got invited to a royal dinner at the castle with other ambassadors of sport.”

The Duke of Cambridge in fact the instigator when the self-proclaimed Scandinavian prince met the proper thing in Norway, Carew managed to find the hearts of those who many football fans didn’t realise could feel the embrace of the game.

The future King of England has long been known to support the famous Aston Villa, even if his selection of club might be confusing from the outside. The Prince has previously described his allegiance to Villa for the crave of a rollercoaster relationship rather than opting for easier weekends throughout the course of the season.

“A long time ago at school, I got into football big time,” Wills said in an interview with Gary Lineker in 2015. “I was looking around for clubs. All my friends at school were either Man United fans or Chelsea fans and I didn’t want to follow the run of the mill teams.”

It’s no surprise that friendly giant Carew was able to turn the Prince into avid footy fan, such is his infectious personality and likability. No longer the ‘The Hulk’ or ‘Ell Vikingo’ either when the former Villa player had paid visits to the local hospice, Acorns.

“He turned up late last time,” says one of the workers at Acorns in 2010. “But he ended up staying later than anyone else. He was here for hours.”

“We can’t kid ourselves as to why we are here,” Carew said.

“We have to take the time to be with the children, to give them a happy day. It’s not pleasant to see children like this but it’s very important to be here, here to make them smile. I’m sure they have looked forward to it for a long time and you have to do your best to give them a great day, a day they deserve, and make an impression.”

His naturally stern face softens somewhat when he walks into the Selly Oak multi-sensory room to greet children proudly wearing their Aston Villa shirts. He might’ve developed the odd battle scar from a decade of bruising encounters with defenders in six countries, even after being called a “handful” by Fabio Cannavaro, but Carew takes charitable responsibilities very seriously.

From the age of only 17, Carew also worked with an anti-racism group in Norway, which had been set up by his friend Farid Bouras.

“Working with youths who are supposed to go to jail but who are taken to a place where they can work, study, read,” is something Carew had been a supporter for during his playing career.

In November 1998, having just turned 19, Carew also became the first black player to represent Norway, leading from example on the pitch too. He wants that responsibility to make a change in the world.

Wherever Carew’s post-football career has taken him, whether it be dining with royals, acting in blockbusters, or simply exploring the beautiful fjords in his homeland, his influence on people never fails to wear, and Aston Villa are so fortunate to call him one of their own.

The post Aston Villa favourite John Carew and his nomadic career appeared first on AVFC – Avillafan.com – Aston Villa Fansite, Blog, & Forum...